Learning Lessons from Immigration

Immigration comes with both the opportunity of starting a new life, the challenge of finding ways to belong in a new country and the need to overcome the fear of outsiders that immigration can engender in a society.

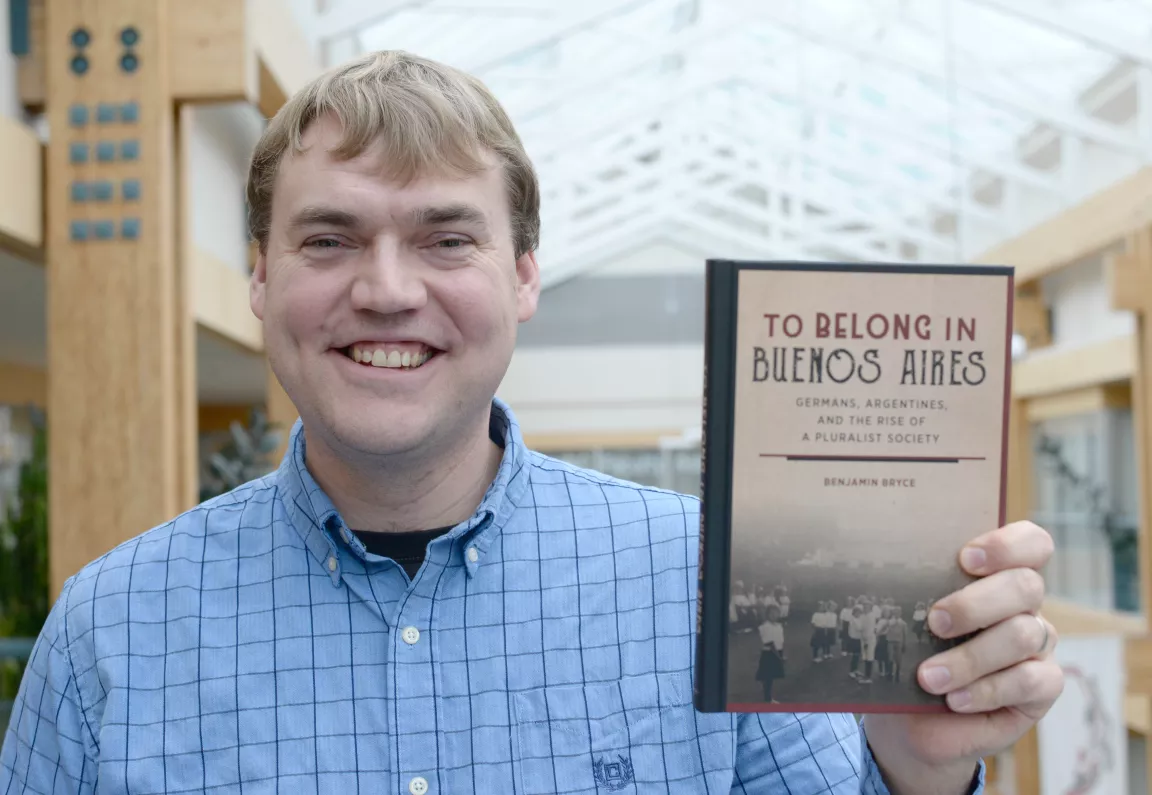

In his new book To Belong in Buenos Aires, University of Northern British Columbia Assistant Professor of History Dr. Benjamin Bryce explores how German immigrants to Argentina created their own institutions to adapt to their new country while at the same time maintaining important links with their homeland. Drawing upon a decade of research into the multiple waves of German migration in the 19th and 20th centuries, Bryce discovered the immigrants forged a lasting German-Argentine identity which proved they desired to be part of the larger society.

“The Germans didn’t think of themselves as all that different, or wanting to stay all that different, from Argentine society,” Bryce says. “They made an effort to make Argentina a culturally plural place long into the future.”

The waves of immigration from Germany and other European cultures stoked fears in some corners of Argentina that the newcomers would be unable to adapt. Through his research in dozens of archives on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, Bryce discovered that through education, religion, language and social welfare, the German immigrants were able to raise a generation of children who the immigrants considered truly Argentine, but who still understood and appreciated their German roots.

The German immigrants established schools, churches and even a hospital. Those institutions have stood the test of time, but have adapted over the years.

“The institutions have been able to carry on, navigating between their German heritage and their Argentine identity,” Bryce says.

German is still taught in many of the schools, although very few of the students are native German speakers. The Lutheran churches established by the immigrants are still standing, but many are now host Spanish-speaking Protestant congregations. The German hospital in Buenos Aries is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, and although the signage remains bilingual, the day-to-day language in the facility is Spanish.

Bryce sees the lasting success of these institutions as proof that, in time, immigrants can help foster a pluralistic society and overcome the fears created by their arrival.

“There is an idea that these immigrants, because they are culturally different, are not part of the nation and they don’t want to be part of the nation,” Bryce says. “But looking back 100 years later, you see that fear is misplaced. There are plenty of lessons about fears of immigration in the nationalist discourse. Those fears prove misguided in the long run.”

The monograph follows up on another book Bryce co-edited, Making Citizens in Argentina, published this past summer. In that book eight scholars from around the world explore the evolving meaning of citizenship in Argentina from the 1880s to the 1980s.

Bryce received support for his research from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the German Academic Exchange Service.